Friday, October 31, 2014

Comics and Caricature

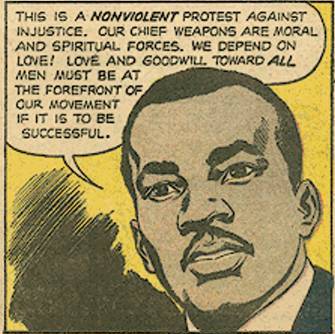

We discussed this topic a bit in reference to Maus, but it's important to revisit as we read both Tomine's Shortcomings and Gene Yang's American Born Chinese. In radically different ways, both texts look directly at questions of race, racial stereotypes, and, in the case of Yang's work, caricature. In Shortcomings, we see a number of characters who are anxious about the politics of interracial dating and the identification of Asian American men with a compromised masculinity (one insidious stereotype Tomine explores through his unsympathetic narrator). How else does Tomine explore race and valences of race as they relate to gender and sexuality in Shortcomings?

Moreover, on a broader level, how do all comics artists have to contend with the history of caricature in their comics? As we discussed early in the semester, cartoons function so effectively because they work through amplification, eg a character might have oversize or even grotesque features that don't conform to how real people look in order to encourage reader projection or identification. What effect does this have on how comics artists draw race?

In the U.S., as some of the images below attest, there has been a long and deeply troubling history of representing Asian Americans (and dealing with anxieties about immigration and ethnic difference) through caricature.

How do Tomine and, as we will see, Yang deal with this issue in their work, if they do so at all? How does this question of racial (or other identity-based) caricature hang over a lot of the work we've read this semester? How does work like the Asian American superhero anthology attempt to subvert stereotypes associated with Asian American identity, particularly those related to gender?

As some of the exhibits below demonstrate, many groups, especially African Americans and new immigrants to the U.S. (including the Irish), were racialized and subject to caricature during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Trigger warning: These images can be very upsetting!

Check out this:

Exhibit on racist caricature and cartoons

Site on caricature of Asian Americans called "yellow-face"

Slideshow of racist caricature in commercials

Archive of Caricature of the Irish

Interesting article on the politics of caricature

Wednesday, October 29, 2014

Crepe Expectations

What did you guys think of the transition from the illustration style of King to Shortcomings? I was a bit thrown off; King had such a complicated, dark style while Shortcomings has a very typical, cartoony style.

Shortcomings deals with race in a very different way than basically any of the stories we have read so far. It is the first we have read set in more contemporary times, and the first to discuss Asian-American culture. After reading three books about African-American and black culture, how do you read this text differently? How does Tomine discuss issues of race differently than Johnson and Pleece, Cruse, or Anderson?

What do you think about the importance of or emphasis placed in stereotypes? This novel seems so rooted in it through Ben's character; discuss!

Is Ben trying to live out a fantasy of being with a white woman, is he just done with Miko, or does he hate himself so much that he wants nothing to do with even his heritage? There is a lot to say about a person's attractions.

And lastly, do you think the title just relates back to Ben and Miko's relationship, as far as we can tell now? Neither is reaching their full potential with the other person nor supporting the other in the proper way.

Discuss relationships, stereotypes, Asian-American culture, and self-loathing in response to this post, basically!

Background Profile

The first thing that struck me about Adrian Tomine's Shortcomings was the title page. Tomine displayed, or what I assume, all the main characters of the book right under the title facing the left in profile with their name, age, height and place of birth.

He essentially gives the initial profile of each character from the beginning, rather than using the text and images to tell us, the reader, this basic but important info. I often found myself flipping back to this page to check the characters as they were introduced and revealed more about themselves.

Did this initial profile view of the character strike anyone else? Did you pay attention to this page as an important indicator of the characters? When viewing this page I automatically thought of the way we, modern society, have access to everyone's basic, even in depth at times, through social media. Do think Tomine had this in mind while making this page? How does this page affect your view of the characters as individuals? Lastly, do you think pages like this is important in a modern comic where society is so obsessed with size, looks, gender and overall profile of person?

He essentially gives the initial profile of each character from the beginning, rather than using the text and images to tell us, the reader, this basic but important info. I often found myself flipping back to this page to check the characters as they were introduced and revealed more about themselves.

Did this initial profile view of the character strike anyone else? Did you pay attention to this page as an important indicator of the characters? When viewing this page I automatically thought of the way we, modern society, have access to everyone's basic, even in depth at times, through social media. Do think Tomine had this in mind while making this page? How does this page affect your view of the characters as individuals? Lastly, do you think pages like this is important in a modern comic where society is so obsessed with size, looks, gender and overall profile of person?

"Protagonist"

For the most part, the novels that we have been reading have been centered around some pretty altruistic protagonists (I mean, we can count Martin Luther King amongst them, for god's sake). Sure, they might say or do things that we don't agree with from time-to-time, but for the most part we can consider them to be unquestionably "good people."

Shortcomings offers a very different kind of protagonist than what we have seen so far. Ben Tanaka edges very close to being a true narcissist; he seems almost exclusively interested in only his own personal problems, non-receptive to the feelings and emotions of others, and seemingly incapable of dealing with people in way that doesn't demean, mock, or somehow otherwise belittle them. Most of his problems stem from flaws in his own personality, but he seems incapable of understanding this, and thus, incapable of addressing the issues. Even in the small section we have read, there are no less than three separate scenes where major arguments flare up between Ben and Miko, simply because Ben is unable to take any measure of criticism.

How does this affect your reading of Shortcomings? Does following such a selfish character make the book more difficult to read, or does it make it more engaging? Do you see any of your own personality traits in Ben, or any other characters in the book? Do those personality flaws make the characters more relatable in some way? Or am I completely off the mark, and is Ben just misunderstood?

Shortcomings offers a very different kind of protagonist than what we have seen so far. Ben Tanaka edges very close to being a true narcissist; he seems almost exclusively interested in only his own personal problems, non-receptive to the feelings and emotions of others, and seemingly incapable of dealing with people in way that doesn't demean, mock, or somehow otherwise belittle them. Most of his problems stem from flaws in his own personality, but he seems incapable of understanding this, and thus, incapable of addressing the issues. Even in the small section we have read, there are no less than three separate scenes where major arguments flare up between Ben and Miko, simply because Ben is unable to take any measure of criticism.

How does this affect your reading of Shortcomings? Does following such a selfish character make the book more difficult to read, or does it make it more engaging? Do you see any of your own personality traits in Ben, or any other characters in the book? Do those personality flaws make the characters more relatable in some way? Or am I completely off the mark, and is Ben just misunderstood?

Sunday, October 26, 2014

The Life of Martin Luther King

It’s obvious from the introduction of the comic that Anderson cares a lot for the direction his art takes in the books and that there is meaning whenever the way the characters are drawn and colored change. After the comic book covers the events of the march on Washington the art style takes a drastic change. In particular there is a heavy use of color not seen often through the first half the comic. Why do you think Anderson chose to do this and how does it affect your reading of the events that followed the march on Washington?

Along the same line of thought why do you think Anderson

left this bubble in the comic? Does it show his concern for detail or is it

merely a way of poking fun at his own pickiness?

For the sake of keeping of curriculum or simply to cover

large periods of time within a school year it does not feel historical events

are given they deserve especially something as momentous as the civil right

movements. Because this people know of the events and Martin Luther King in a

general sense but not in depth. Would you say the comic serves as a deeper

learning experience about the civil rights movement and King or does it barely

scratch the surface? Do you think it that Stuck Rubber Baby, Incognegro, and

King complement each other as far as covering the topic of racial issues or

does King surpass them because it revolves around actual events?

Friday, October 24, 2014

King, by Ho Che Anderson

As you may have noticed, King differs greatly from a number of other texts we've read this semester--both in its visuals, its composition, and its storytelling choices.

Early in the semester, you had a great conversation about the differences (such as they are) between "high" and "low" art, and how comics is often left to straddle divide between the two. This conversation questioned the very notion of constructing boundaries between mass and elite cultural production, even as many of you admitted that the ideas of high and low continue to filter into how we appreciated and categorize art. (Think of visiting "Half-Price Books," for instance--how does the store's shelf categorization suggest something about the place of genre fiction (such as crime fiction, romances, etc.) as compared to what we deem "literary fiction"?). How does King borrow from the conventions of both "high" and "low" art, as well as the vocabulary of film, to tell MLK's story? Is King more like the sort of visual art you'd see hanging in a museum or gallery than what you'd usually associated with the visual universe of comics? For those of you who have the big, "special edition" of the text, how does the "making of" section in the back of the book affect your sense of Anderson's project in constructing King?

Moreover, as I will outline further in my podcast, King differs from the other works we've read because it tells the story not of a random individual (as Maus and Persepolis do) or of a group seeking rights (as Stuck Rubber Baby does), but of an iconic figure that many of us have already encountered in written or visual form (t.v., film, photography). How does the fact that King is about an iconic figure affect your reading of the text? How does it affect Anderson's use of visuals and storytelling technique? What do you make of his opening of the text with young MLK, his use of the "chorus" of commentators on MLK, the stark black and white palette (mixed with the occasional use of color) employed throughout the book, and his introduction of photographs, however blurry, into the text? Perhaps, most strikingly, what do you think about Anderson's choice to show the darker side of King in terms of his extramarital affairs? Please use the space below to comment on some of these questions about King.

I know this text is a challenging one, and I will use my podcast and some further blog posts to help us make sense of it.

Tuesday, October 21, 2014

What's in a Label?

What's in a Name Label?

First of all, I want to apologize for the late post! This

post is referring specifically to pages 1-103 in Stuck Rubber Baby.

Labeling race and sexual orientation through name calling,

is a theme in Stuck Rubber Baby that immediately

stood out to me. On the third page of the novel, a conversation with Tolend

Polk’s parents set up the distinction that certain names should not be used:

Throughout the book’s dialogue the characters seem to

consider “negro” as a more acceptable label. However, that term is now

considered politically incorrect and currently people are taught to use

African-American. Outside of the character’s dialogue, Polk as a narrator uses “black”

to describe the community. These terms are in stark contrast on page 14:

Polk’s father and mother set up the need for distinction

between offensive and acceptable labels for different members in the community.

The language from the “Kennedy Time” and when Stuck Rubber Baby was published show a large change in how we talk

about and identify race in America. The way the novel labels sexual orientation

in the context of offensive or politically correct is also introduced in the

novel on page 6:

I have several questions I wanted to address while reading Stuck Rubber Baby and noticing the

labels, but primarily were so we draw the distinction between offensive and

correct or joking? Is it an individual decision based on personal experience

with such loaded words? Is it the historical context and its etymology a sole

or significant factor in a label’s appropriateness?

I recently saw an interview that made me wonder if our language,

and our culture, is evolving to a point where labeling differences are not

needed. If this is the case, how do we decide what labels to use when describing

historical events?

Howard Cruse does a great job of using different labels to evoke

different feelings within the reader, or even develop certain characters based

on their labeling of other people. I mentioned a few moments, but where are

some other frames in Stuck Rubber Baby when

he does this? What is his goal in using the specific language in those frames?

Friday, October 17, 2014

Civil Rights and LGBT Rights/ Questions about Stuck Rubber Baby

Throughout Stuck Rubber Baby, Cruse draws analogies between civil right and the rights of LGBT people. Do you think this analogy is appropriate? How does the connection he draws help to illuminate the connections between race, gender, and sexuality? How does the theme of secrecy about sexual orientation in Stuck Rubber Baby relate/ not relate to the way Johnson and Pleece portray racial passing in Incognegro?

In order to help answer these questions and understand the timeline of what Cruse narrates in his graphic novel, please take a look at these links with the timelines for civil rights and gay rights in the U.S.

There's also an interesting NPR piece about the analogies between civil rights and the gay marriage.

You're reading an (almost) banned book and other facts about Stuck Rubber Baby

In 2005, along with other books with gay themes, Stuck Rubber Baby was almost banned by a Texas library.

Cruse talks about being a pioneering gay artist, among other topics, in this interview with the Comics Reporter, as well as this one with Publisher's weeklyupon the reissue of Stuck Rubber Baby.

Here's Howard Cruse's site.

More on Cruse and LGBT identity in comics

Article on LGBT representation in American comics, Part 1 and Part 2

Wednesday, October 15, 2014

Stuck Rubber Baby: Sketching Out Thoughts

Stuck Rubber Baby has a very different style than any of the novels we have read so far. I want you to discuss the differences of the storytelling/narration, illustration and layout, and amount of information. Just talk me through what you were thinking while getting acclimated to the new style of the novel. How has this thought process affected how you read the first part of the novel?

The narration of this novel seems to be more literature-based. It is also more inviting, perhaps, than the other novels we have read. What is the effect of the interjections by the man who we are to assume is Toland's current partner? What about the extra details the audience gets from each drawing (sound effects, the stars when Bernard was beaten up, song lyrics…)? What do you enjoy or dislike about all of these new types of information we receive from this book?

I also wanted to see if anyone has any ideas for why Sammy Noone's last name resembles the term no one. Just something to ponder.

Does anyone know why the book has its particular title from reading the story so far?

Just tell everyone what you were thinking while reading; make guesses and discuss them!

Friday, October 10, 2014

Incognegro: Heroism and Justice

If there is anything that I enjoy in any story at

all it is heroism. In most, if not all, stories, movies, TV shows, video games

that I have seen and read, there is always the hero rising up against fear and

doubt to overcome evil a bring a better tomorrow for everyone. This is what I

enjoy to see and is what my inspiration and focus is as a writer. In fact, this

is pretty much what everyone wants to see then it comes to storytelling. Incognegro

was able to display this aspect when describing the events lynchings being

busted by light-colored reporters including Zane. Zane was willing to risk his

life so that the truth can be brought about the lynchings. And Carl wanted to

accompany Zane for his last mission so that he could take his place. Based on

Carl’s personality throughout the story, do you think that Carl wanted to take

Zane’s place when he retired just for the fame, or was there actually a smidge

of humility within him that wanted to see justice? What evidence is there that

supports your thoughts? Also, what did you think of Carl’s death near the end

of the book?

In addition to the process of storytelling, another helpful mechanism to heroism would be the downfall of the villain. For every hero there is always a villain, and everyone wants to see the villain parish either by the hands of the hero, or by poetic justice. As we continue to read, we see the villain, Mr. Huey, for what he truly is and wish for him to get what’s coming to him. So when the book ends, do you believe that the ending was appropriate in poetic justice? What do you make out of the fact that the townsfolk actually believed what Zane wrote about Mr. Huey’s identity? Can people really be that naïve?

Wednesday, October 8, 2014

Midterm Paper Directions and Topics

Midterm Paper –Due Date Nov

1 Engl 3084

General Directions: Write a 6-7

page paper addressing one of the following. Below, please find a number of questions

focusing on the works we’ve read during the first half of the term. It’s important that your readings from Scott

McCloud factor into your essay. Use the

terminology McCloud introduces in Understanding

Comics to unpack the particularities of the text you choose to

explore. You may also want to use

scanned or photocopied images to support your argument. These images will be in addition to the 6

page minimum, rather than a part of the 6 pages. We can discuss how to “quote”

from images. If you would like to use other theoretical sources on comics, I

can help you find them.

Some general guidelines:

Handing in your paper late will lower your grade. As a rule, it is good

to avoid using the first person in a formal paper. Be certain to use spelling and grammar check

on your computer; I am expecting that I will not have to focus unduly on this

aspect of your writing when grading your work.

Back up your arguments with quotes from the reading and properly cite

these quotes in MLA format. If you have

questions about citation practice, there are a number of online resources that

can help you and I am happy to give you input, as well. If you wish to work on a topic not listed

below, just make sure to discuss it with me before beginning the work so we

ensure it is narrow enough to fit within such a short paper. I would be pleased to meet with you over the

course of the next weeks to discuss your midterm paper if it would be helpful.

Do not plagiarize! I am expecting that you won’t, but, if you do, it results in

an automatic “F.”

Maus:

- History, both global and personal, plays a large role in Maus. What is the relationship between personal history and global history in this text? How does Spiegelman balance narration of personal history and larger world historical events? How is the loss of his mother’s diary used as a thread to connect these two forms of history? How do the different genres evident in Spiegelman’s text – testimony, oral narrative, maps – work to do the same? Using specific examples, talk about how Spiegelman’s narrative choice to interweave losses both personal and large-scale works in Maus.

- We mentioned in our discussion online that artists who wish to represent the Holocaust and the havoc it wreaked on its victims and survivors have a daunting task. How does Spiegelman’s choice to represent the Holocaust in the form of a graphic novel allow him to address/ not address these questions of representation? Does the pictorial form of the graphic novel provide Spiegelman with a way of meditating on questions of representation? If so, how? Give specific examples and explain how they link to the larger issues surrounding representation of trauma.

- Framing devices are very important to how we read and understand Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Most significant of the framing devices in the text is Art’s relationship with Vladek, which structures how we, as readers, interpret the novel, comprised as it is of testimony he collects from his aging Holocaust survivor father. Keeping the importance of framing devices in Spiegelman’s work in mind, what do you make of the epigraphs that begin each volume of Maus? How do they work to introduce and structure our reading of the text? How do they create or disrupt continuity between the volumes? Use Spiegelman’s epigraphs to explore Maus and the role of framing in the text.

- Art Spiegelman’s choice to portray the conflict between Nazi and Jew in World War II era Europe as a battle between cat and mouse drew much attention when Maus was published. How does Spiegelman’s use of animals to represent national or ethnic types work in Maus? Use close readings of a few scenes in the text to explain how Spiegelman’s animal characters allow him to comment on the historical circumstances of the war and the place of racial-thinking in it.

Persepolis:

1.

Both Maus and

Persepolis

are memoirs written in graphic narrative form.

However, Spiegelman and Satrapi’s narratives differ in key ways. How does Satrapi’s choice to frame the story

of the Islamic Revolution in Iran

through the eyes of a child affect your reading of her story? How does this choice contrast with

Spiegelman’s more cynical, by-proxy narrative of the Holocaust? How do Spiegelman and Satrapi use imagery

differently/ similarly?

2.

Satrapi’s Persepolis

proves unique in the comics genre because it is centered on the viewpoint of a

female child and, later, young woman.

How does gender factor into your experience of Persepolis? Does Satrapi suggest something about the ways

in which revolutions affect women in particular? How does Satrapi’s focus on

female experience challenge our idea about the conventions of comics?

3.

Persepolis is

very much a narrative about place and the role it plays in the formation of

identity. The characters in Satrapi’s

memoir struggle to stay in a chaotic homeland or deal with the complexities of

exile. How does Satrapi use the physical

space of the comic to comment on the power of geography during a period of

social tumult?

Incognegro:

1. Incognegro foregrounds the experience of

passing in American culture. What sorts

of passing take place in the graphic narrative and how do Johnson and Pleece

use the visual nature of the medium to make a commentary on the optics of race

and the discourse of visibility in America? How might Chaney-Lopez’s piece on the

construction of race be useful in reading this text?

2. Johnson

begins Incognegro with a foreword,

just as Satrapi begins Persepolis. How do these forewords frame your reading of

the texts to come? How are they similar? How different? What about the form of

the graphic narrative seems to encourage this type of explanation?

3. Incognegro depicts a number of scenes of

lynching. How do Pleece and Johnson

choose to depict this racialized violence? How do their illustrations compare/

not compare to the many photographs of lynching that were disseminated during

the same time period?

Stuck Rubber Baby:

1. In

Stuck Rubber Baby, Howard Cruse

compares the civil rights movement with burgeoning movements around GLBT

rights. What point does he make in this comparison? How does the graphic medium

allow him to draw out this comparison? How does his work illustrate the theme

of intersectionality as articulated by Crenshaw?

2. Stuck Rubber Baby is one of the earliest

works we’re reading in class. How does it mark the early days of the graphic

narrative/ graphic novel movement? How does it compare to other books we’ve

read stylistically and thematically? Pick one other text and make a detailed comparison.

King:

1. We

are used to seeing photographic representations and cinematic images of Martin Luther

King, Jr. How does Ho Che Anderson use

these images to create his visual narrative in King? How does King’s iconic status affect the way we read Anderson’s graphic

depictions? Does the comics version of

King expand the conventional narrative of his life?

2. While

both Maus and Persepolis

deal with ethnicity and national identity in different ways, King is the first work we’re reading

that explicitly deals with questions of race and American culture. Explain how the visual nature of Anderson’s text provides

a commentary on race relations during King’s time.

Monday, October 6, 2014

Resources on passing

Article on the history of passing from the New York Times

Piece on passing and the American dream

The problem with passing

Definition of and links on one-drop rule

PBS's "Who Is Black?"

wiki on one-drop

Kailynn's Post

Kailynn was having some trouble posting to blogger today. Here is her post.

Identity and Incognegro

One of the main themes in Incognegro is identity. Zane is constantly under a false identity

whether he is in the field—undercover—or he is at work—using the pseudonym of

Incognegro. His fair skin allows him to pass as “white”. He describes his

transformation on page 18. What do you think Zane’s reaction to this is and is

he able to be himself at all? How do you think this makes him feel? Do you feel

as if he is losing his identity as a black male because of pretending he is

white? How do you think he keeps composure when he is around white people that

degrade his own race? Due to Zane’s false identity, do you often see yourself

getting confused as to which race he is portraying each time?

I found it difficult at times to follow the storyline

especially when the story jumps from one scene to the next without a warning

signal. For example, when Zane crosses the path of the woman that shoots him,

then changes to his encounter with his brother at the train station, then back

to the woman—just within a couple of pages. I had to look back a few times to

see where Johnson and Pleece were going with this.

Lastly, the major aspect that stood out to me in this

graphic novel is the art involved. It’s very different from the other graphic

novels we have read. It reminds of a Sin

City-esque feel. I really enjoy it. I feel as if the graphics are very

detailed especially with facial expressions—whereas with the other graphic

novels we have read, it is hard to see emotions on the characters’ faces.

Podcast on Incognegro

A podcast I made about some of the issues introduced by Incognegro. Let me know what you think!

Sunday, October 5, 2014

Matters of Identity

It seems that when people don't know you, you can be who ever you want to be. It may be fine at first but as time goes on people may find out who you really are. The story of Incognegro seems to illustrate this point, at least to me. Johnson takes this matter and ramps it up a bit by putting serious consequences on it. The story seems to be a sort of warning against using your identity to deceive people. I say this because out of all those who assumed different personalities only Zane came out alive, this includes Francis. Do you agree that Johnson's Incognegro is a warning against taking on different identities in or order to deceive? And if you do agree consider this, even though Zane's assumed identity was doing a service to the community by pointing out those who attended lynching, do you think that it was justified according to the message highlighted in the book?

Friday, October 3, 2014

Film v. Comics

For those of you interested in the relationship between film studies and comics studies, check out this article in the Journal of Cinema Studies.

If you're interested in questions of medium, take a look here.

This introduction to graphic narrative also looks at film and comics a bit.

Thursday, October 2, 2014

Persepolis as a Universal Narrative

Most movie adaptions do not usually have the author directly involved. The rights are given away to a movie studio and the plot along with its characters is alerted however the producers see fit even at the expense of real events if the adapted story is a biography. As Persepolis an independent film, however, Satrapi was able to direct her graphic novel's adaption and I believe that puts a whole new aspect in how the movie was handled. I did a little research on the movie and Satrapi mentioned that she left the parts of the movie dealing with the past in black and white so that the movie could be more universal and show that the events of the revolution could happen in any country. Do you think the movie accomplishes this or does it still stand as a movie that focuses primarily on Iran?

As Oliver mentioned the movie did not seem to focus much on Satrapi’s personal struggles. A lot of the scenes and characters were either downsized or left out entirely making the whole experience feels sped up for the sake of time. Since Satrapi was aiming to make the story more universal as the movie would likely reach a completely different audience than the graphic novel I argue that she left in just enough of her personal life to keep the story hers while also allowing the audience a chance to see life through Marji’s eyes without the intrusion of too much narration. Do you think that the movie allows the viewer a better chance to see the events through Marji’s eyes or is the effect of the story completely lost without more of Marji’s narration?

As Oliver mentioned the movie did not seem to focus much on Satrapi’s personal struggles. A lot of the scenes and characters were either downsized or left out entirely making the whole experience feels sped up for the sake of time. Since Satrapi was aiming to make the story more universal as the movie would likely reach a completely different audience than the graphic novel I argue that she left in just enough of her personal life to keep the story hers while also allowing the audience a chance to see life through Marji’s eyes without the intrusion of too much narration. Do you think that the movie allows the viewer a better chance to see the events through Marji’s eyes or is the effect of the story completely lost without more of Marji’s narration?

The Film Versus the Book

Having now seen the movie, and reading Persepolis, there is a question that comes to my mind. Which is more effective at delivering Marjane's story? Does one do more justice than the other?

Personally, I found the movie highlighting different areas than that of the book. Similar to my earlier post, in terms of the beginning parts of the film, the specific events during school, and the troubles she faced within were barely touched upon. Did others find parts the felt integral to the story and its message being left out or just barely touched upon?

Lastly, having watched the film on YouTube, there was an additional aspect, the comments section. I am not sure if anyone took the time to read through them (I would encourage you too), but I find that the comments are an interesting source of other inputs. A small insight as to what others take from videos, similar to our discussions here in class. How do you find these outlooks to intersect with ours? Is that format an aid or does it detract from more productive forms of discussion?

Personally, I found the movie highlighting different areas than that of the book. Similar to my earlier post, in terms of the beginning parts of the film, the specific events during school, and the troubles she faced within were barely touched upon. Did others find parts the felt integral to the story and its message being left out or just barely touched upon?

Lastly, having watched the film on YouTube, there was an additional aspect, the comments section. I am not sure if anyone took the time to read through them (I would encourage you too), but I find that the comments are an interesting source of other inputs. A small insight as to what others take from videos, similar to our discussions here in class. How do you find these outlooks to intersect with ours? Is that format an aid or does it detract from more productive forms of discussion?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)